Architectural research is a fun aspect of writing historical fiction. The best is when you’re able to walk the streets and corridors that your characters would have walked, burrowing into that sense of place.

Unfortunately, especially for those of who write stories set hundreds of years ago, sometimes the buildings have been significantly changed—or have disappeared altogether.

For my Tudor suspense novel, set in 1565, the climax of the story takes place in Whitehall Palace, once Europe’s largest palace, and now a hulking warren of government buildings with a few remaining historical bits. So, how do I (and my characters) walk the halls of a palace that no longer exists?

Whitehall Palace history

Whitehall was once a jewel of British architecture. The Archbishop of York built what he called York Place in the 1240s on land in Westminster, near London. When Cardinal Thomas Wolsey took it over in the early 15th century, he extensively rebuilt it. In 1530, King Henry VIII removed Wolsey from power and took over the palace, further expanding it. The name “Whitehall” was first mentioned in 1532.

Henry spent £30,000 in the 1540s in renovations, equivalent to about £26 million in today’s money. He married Anne Boleyn in the chapel at Whitehall (ironic, given the reason for Wolsey’s downfall was his failure to get the Pope to grant an annulment from Henry’s first wife, Catherine of Aragon), and Henry died at the palace in 1547.

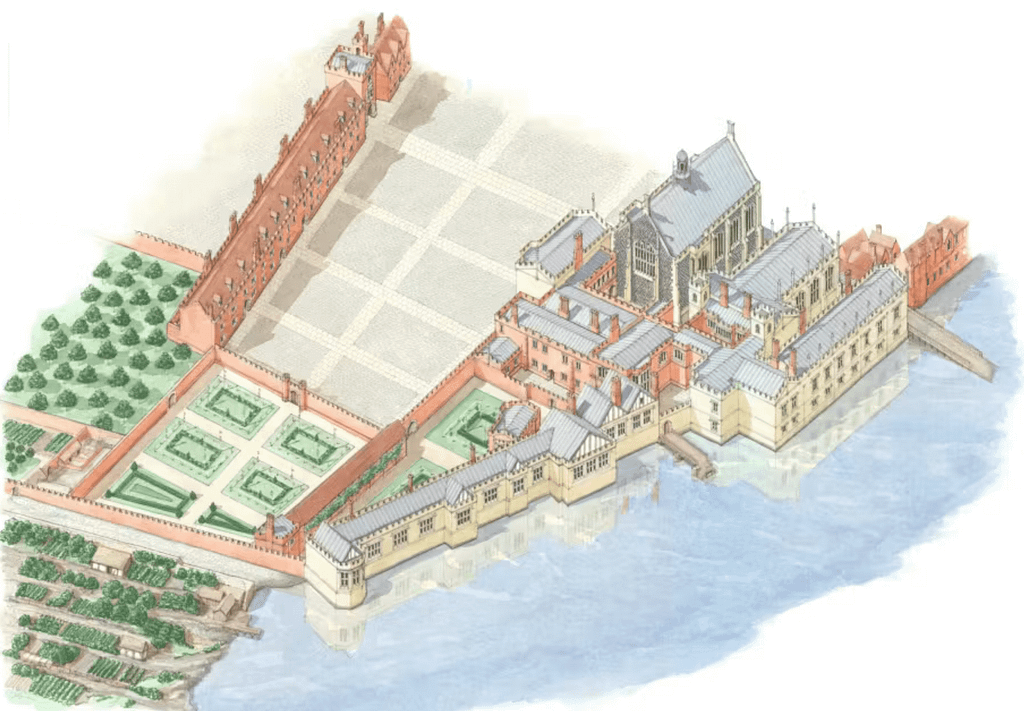

By the time Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn’s daughter Elizabeth sat on the throne, Whitehall was the largest palace in Europe. The palace was divided physically and functionally into two distinct sections: the main buildings on the east (river) side and the entertainment buildings on the west (park) side. At either end, Henry had two monumental gatehouses constructed.

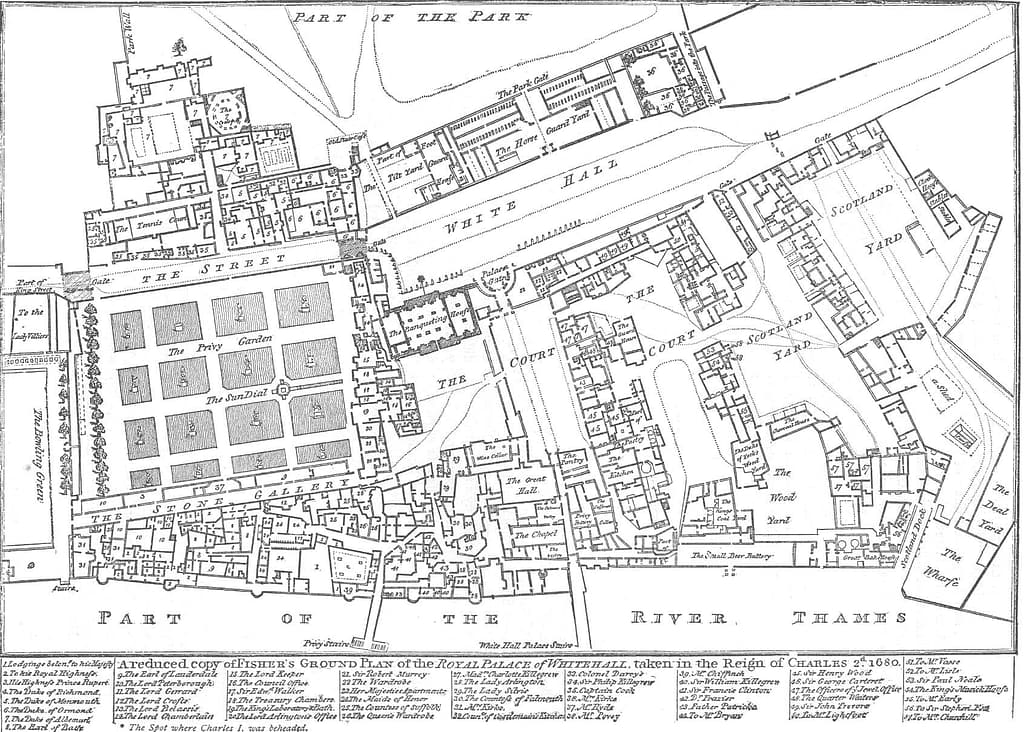

The primary approach to the palace was via the Thames River. Riparian travel was a common way to get around London and its environs—faster and often more efficient than traveling by congested, and often risky, roads. An elaborate system of water stairs lined the Thames. At Whitehall, simple wooden stairs were available for the public, but dignitaries used the Privy Stairs, a double-tiered pier extending into the Thames. There was also an entry point near the working part of the palace called the Scotland Dock, which my protagonist uses in a moment of urgency.

The gardens at Whitehall were also a showpiece. The Privy Gardens lay to the south of the buildings. Throughout the decades, the gardens were expanded and made more elaborate. Several pivotal scenes in the last third of my story take place while accompanying the queen on her daily walks in the gardens.

Roaming the halls of a bygone palace

Whitehall Palace was mostly destroyed by a fire in 1698, so it’s not possible to walk the halls or gardens today. I had to rely on maps and historical documents. Luckily, because it was such an impressive palace, several contemporary sources exist for people describing the layout and features.

At one point in my story, my protagonist escapes from the room where she’s been imprisoned and has to sneak through the palace to get to the stables. This made for a fun research exercise to trace her route through the palace using old maps of the rooms and grounds. At one point, she passes the small beer buttery and great bakehouse. Of course, the small beer buttery sent me down a research rabbit hole. A buttery was where they stored the “butts” (barrels) of beer. Small beer is a lager or ale containing lower alcohol levels and was often drunk throughout the day, from breakfast on, in lieu of water, which was considered unhealthy or unsafe to drink. It was common from the Middle Ages into the 19th century.

Bringing a lost place back to life enables us to build a more tangible world for our story and characters. One of the most fun things about writing historical fiction is walking these long-forgotten paths in our minds… and letting our readers go there with us.

Resources

British History Online is a repository of 1,300 primary and secondary sources, 40,000 images, and 10,000 map tiles relating to British and Irish history. During the pandemic (when I wrote my first Tudor suspense novel), BHO made all of these online sources free. There is a subscription model now, but a lot of the resources are still free to access.

The Agas Map is an extremely detailed digitized map of a 1561 woodcut. You can zoom in to see the minutest details. This has to be one of my all-time favorite sources for moving characters around in London.

From Palace to Power: An Illustrated History of Whitehall by Susan Foreman

Featured image: mid-17th century etching of Whitehall Palace, source: Wikimedia Commons

Leave a Reply